Khi bạn tìm kiếm một nhà cái uy tín để tham gia vào thế giới cá cược trực tuyến, không thể bỏ qua sự tỏa sáng của nhà cái uy tín K9WIN. Với cam kết về tính minh bạch, sự an toàn cũng như trải nghiệm chất lượng, nơi đây không chỉ là một nhà cái mà còn là điểm đến lý tưởng cho những người đam mê cá cược. Hãy cùng chúng tôi khám phá tại sao sân chơi này đã xây dựng danh tiếng của mình như một lá cờ dẫn đầu trong ngành!

Nhà cái uy tín là những công ty hoặc tổ chức cung cấp dịch vụ cá cược trực tuyến mà đã được chứng nhận là đáng tin cậy, có sự giám sát cũng như tuân thủ quy định của cơ quan quản lý, có lịch sử tích lũy của việc trả tiền và đối xử công bằng với người chơi.

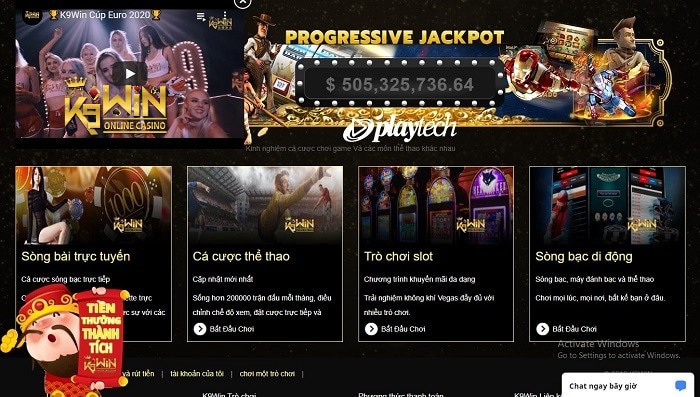

Nhà cái uy tín K9WIN, một doanh nghiệp hoạt động trong lĩnh vực giải trí cờ bạc, chính thức ra mắt vào năm 2012, thuộc sự giám sát của tập đoàn PAGCOR tại Philippines. Tuy nhiên, trong thời gian gần đây, cổng game đã chứng tỏ sự phát triển đáng kể tại thị trường Việt Nam. Điều đáng chú ý là họ đã đầu tư đáng kể vào việc quảng cáo và thương hiệu hóa, qua đó đã mở rộng sự đa dạng hóa sản phẩm của họ.

Bên cạnh những ưu điểm của trang cá cược uy tín K9WIN thì vẫn còn tồn tại những nhược điểm cần khắc phục:

Ưu điểm | Nhược điểm |

Sự đa dạng trong lựa chọn cược trận đấu thể thao. | Hiện tại, nhà cái chưa hỗ trợ live streaming. |

Giao diện trang chủ đã được tối ưu hoá với ngôn ngữ tiếng Việt. | Giới hạn đi mất số tiền cược tối đa cho người mới chơi |

Hợp tác với nhiều mô hình cung cấp đánh cược uy tín. | Chưa phát triển được ứng dụng cá cược thể thao cho điện thoại. |

Với hơn 60,000 sự kiện thể thao được tổ chức mỗi tháng, người chơi tại đây có sự đa dạng tuyệt vời khi chọn lựa các môn thể thao để tìm kiếm mức cược hấp dẫn phù hợp với sở thích của họ. Ngoài ra, kho game còn đầy ấp:

Hiện tại, nhà cái uy tín này đang cung cấp một loạt các chương trình ưu đãi hấp dẫn dành cho các thành viên của họ. Trong danh sách này, các chương trình khuyến mãi phổ biến bao gồm:

Đâu là lời giải thích cho câu hỏi trên? Chúng tôi mời bạn điểm qua một số ưu thế mạnh nhất có thể lôi cuốn người chơi tại trang cá cược này như là:

Khi bước vào trang web, người chơi sẽ ngay lập tức bị cuốn hút bởi giao diện đẹp mắt có bố cục thiết kế đơn giản nhưng vô cùng tinh tế, quyến rũ. Nền tảng của trang web này nổi bật, mang vẻ hiện đại, đẳng cấp, gần như giống như một nơi xa xỉ trên đại lộ Las Vegas.

Bộ sưu tập game tại trang cá cược trực tuyến này sẽ khiến người chơi hoàn toàn thụ động bởi sự đa dạng. lôi cuốn. Sân chơi này đã kết hợp cùng những đối tác hàng đầu toàn cầu trong lĩnh vực cung cấp game, nên tất cả các thể loại game đều được lựa chọn kỹ càng, với chất lượng tối ưu, mang đến cho người chơi những trải nghiệm hứa hẹn không giới hạn.

Quy trình giao dịch tại nhà cái uy tín này được tạo ra với tính đơn giản, tiện lợi cùng với tốc độ nhanh chóng. Ngay từ bước đầu tiên của quá trình đăng ký tài khoản, việc tạo ra tài khoản cũng diễn ra dễ dàng nên không tạo ra bất kỳ sự phiền toái nào cho người chơi.

Một trong những điểm ưu việt tại đây chính là các chương trình khuyến mãi vô cùng hấp dẫn với đầy lợi ích. Người chơi sẽ được hưởng cơ hội cực lớn để đạt được những kết quả xuất sắc thông qua những chương trình khuyến mãi hàng ngày, hàng tuần,….

Mọi người tham gia trò chơi tại K9WIN đều trải qua sự hài lòng không giới hạn với dịch vụ chăm sóc khách hàng vô cùng tận tâm, chuyên nghiệp. Nhà cái này đặt sự quan tâm và đầu tư lớn vào việc cung cấp dịch vụ chăm sóc khách hàng một cách xuất sắc theo chiến lược đúng đắn.

Nhà cái uy tín K9WIN đã xây dựng danh tiếng quốc tế của mình dựa trên sự xuất sắc trong các trận cược mà họ cung cấp. Với sự đa dạng của loại cược, tỷ lệ cược cao cấp, hỗ trợ chăm sóc khách hàng và các giao dịch nhanh chóng, sân chơi sẽ đáp ứng tất cả các yêu cầu của bạn.